Achieving A Balance Between Public Protection and Public Privacy

By Alan McConnell, Forensic Advisor, Cyan

The importance of digital evidence contained on the personal devices of suspects, victims, and witnesses in assisting Law Enforcement investigate serious crime cannot be understated. However, never has the public’s awareness of their right to protect personal data on their devices (such as tablets, laptops, and smartphones) been as strong as it is today.

While there appears to be a general acceptance of the need for Law Enforcement to obtain digital evidence from personal devices, the recent publication of reports such as “Digital stop and search: how the UK police can secretly download everything from your mobile phone” by Privacy International1, as well as several high-profile news stories questioning the technology Law Enforcement agencies use to obtain digital evidence, have brought the issues involved to mainstream attention.

Digital evidence

In the not-too-distant past, the recovery of digital evidence was the realm of specialist Cybercrime units, investigating cyber dependent crimes such as attacks on computer systems and infrastructure, or cyber enabled crimes where computers were used in the commission of ‘traditional’ crimes.

The proliferation of home computing and mobile digital devices has meant that important digital evidence now potentially exists for most criminal cases. In fact, one senior police manager reporting to the House of Lords Science and Technology Select Committee in 20192 stated that digital evidence now plays a role in 90% of criminal cases.

Such is the volume of potentially relevant digital evidence in criminal cases today, there is a real risk that it could overwhelm Police Forces and the judiciary. To mitigate this risk, many Police Forces have, or are planning to, roll-out digital triage capabilities to front-line officers to help quickly identify those devices that are likely to contain pertinent evidential data and rule out those that do not, reducing the number of devices seized for full forensics examination and the volume of data that must be examined.

This move from individuals’ digital devices only being examined by highly trained expert digital forensic analysts, to potentially being routinely examined for evidence by a much larger group of less experienced Officers, understandably raises concerns around the preservation of private data.

Data privacy

There are few areas of today’s life that do not involve the use of a home computer, mobile phone, or tablet. From taking and storing our holiday photos, work communications and internet banking, to private communications with family and loved ones, our digital devices are at the very centre of our private lives.

These devices are an ever-increasing repository for our personal and sensitive information. A cursory look at my own browsing history, communications, geo-location data and biometric information would piece together to give a surprisingly deep and accurate insight into my social life, state of mind and physical health (thanks for telling me to stand up every hour Apple!).

The data held on my devices is just that: my data. As such, I have every right to expect that my data will not be viewed or used by anyone else without my consent. As a former Police Detective and Digital Forensic Analyst, however, I am acutely aware that the ever-increasing scope of digital forensic capabilities available to Law Enforcement is of immense value when it comes to detecting crimes, securing convictions, and identifying victims. Herein lies the problem.

Collateral intrusion

Traditional techniques for the recovery of digital evidence have generally been rather indiscriminate in what data they obtain from a device. Taking a full forensic image of a computer’s hard drive or external storage device or extracting the full contents of a mobile phone before then searching that data for evidence pertinent to an investigation is standard practice. However, searching through large amounts of data to find a small amount of digital evidence inevitably leads to collateral intrusion, the unintentional gathering of non case-relevant data alongside relevant data, into a person’s private data that is not pertinent to the investigation.

Collateral Intrusion in the context of examining a digital device for evidential data can occur in many ways, but examples include:

- Viewing a suspect’s non-pertinent personal photos while looking for images of Child Sexual Abuse

- Reading communications data outside of the timeframe relevant to the offence being investigated

- The viewing of data on a device that infringes on the privacy of persons not subject to the investigation e.g., acquaintances of the suspect who may appear in photographs

Selective extraction, whereby Law Enforcement need only collect data from a device that is strictly relevant to the case in question, is one approach and potential solution to collateral intrusion, and favoured in particular where concerns have been raised that victims and survivors having their entire phone examined after a serious sexual assault is a disproportionate and unnecessary invasion of their privacy. The challenge therefore is to ensure a balance is struck between the benefits that digital evidence brings, and the new ethical dilemmas created by the techniques used to recover that evidence.

A collaborative approach

These concerns are understood by the Digital Forensic community and in a commentary submitted to the Forensic Science International journal in 20203, a number of updates to the ACPO Good Practice Guide for Digital Evidence4 were proposed, among which was, “All justifiable measures must be taken to limit both collateral intrusion and disruption caused by their investigation.”

The issue of collateral intrusion has also been recognised by UK Policing and earlier this year the College of Policing issued new ‘Authorised Professional Practice’ guidance on the extraction of material form digital devices’5.

The examination of a person’s devices for digital evidence will likely always involve an element of unavoidable collateral intrusion. Law Enforcement will continue to take measures to minimise this with more stringent processes and guidance, but there is also a need for the creators of digital forensic tools to assist by developing tools in direct collaboration with Law Enforcement that can help reduce potential collateral intrusion by allowing focused targeting and extraction of investigation-relative digital evidence only.

A balance can be found between protecting the public by helping identify digital evidence to ensure dangerous offenders are identified and prosecuted, and protecting the public’s right to privacy by helping ensure that the recovery of this digital evidence does not compromise a person’s private data.

By working closely with Law Enforcement, tools need to be developed which give front-line Officers the ability to examine digital devices very quickly, and on-site, for known illegal content while completely protecting the owner’s privacy by only exposing the investigator to case-relevant data.

2 – https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201719/ldselect/ldsctech/333/33302.htm

3 – “ACPO principles for digital evidence: Time for an update?” – Forensic Science International: Reports

Volume 2, December 2020

4 – ACPO Good Practice Guide for Digital Evidence, Version 5 (October 2011) – Association of Chief Police Officers of England, Wales & Northern Ireland

5 – https://www.app.college.police.uk/app-content/extraction-of-material-from-digital-devices/

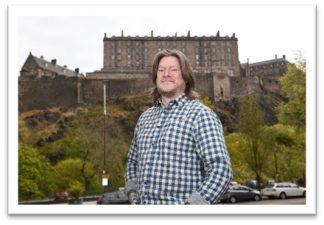

About the Author

Alan McConnell is Forensic Advisor at Cyan. He is an experienced Digital Forensic Analyst with 12 years Law Enforcement experience of conducting forensic and criminal investigations and presenting evidence in court, having served as a Detective and Digital Forensic Analyst for Police Scotland before joining Cyan in 2019. Alan can be reached on Cyan’s twitter @cyanforensics and at our company website https://cyanforensics.com/

Alan McConnell is Forensic Advisor at Cyan. He is an experienced Digital Forensic Analyst with 12 years Law Enforcement experience of conducting forensic and criminal investigations and presenting evidence in court, having served as a Detective and Digital Forensic Analyst for Police Scotland before joining Cyan in 2019. Alan can be reached on Cyan’s twitter @cyanforensics and at our company website https://cyanforensics.com/